Part One: The History of Vaccines

This month, I planned to do a humdinger of a blog on COVID vaccination’s importance and share my personal experience in getting my first dose. But the more I thought about it, I felt it necessary to give context to vaccination and vaccine in general. There is so much out there that provides a wildly divergent opinion, but there is only one correct scientific path to follow. As the most extensive global vaccination program in history rolls out, I thought it essential to note that this monumental undertaking has been done previously, with the most recent undertaking being the Polio program. And now, let us begin our discussion into the history and science of vaccines.

This month, I planned to do a humdinger of a blog on COVID vaccination’s importance and share my personal experience in getting my first dose. But the more I thought about it, I felt it necessary to give context to vaccination and vaccine in general. There is so much out there that provides a wildly divergent opinion, but there is only one correct scientific path to follow. As the most extensive global vaccination program in history rolls out, I thought it essential to note that this monumental undertaking has been done previously, with the most recent undertaking being the Polio program. And now, let us begin our discussion into the history and science of vaccines.

The Definition

The standard dictionary definition gives us the nitty-gritty of the how and a little bit of the why.

vac·cine

/vakˈsēn/

noun

a substance used to stimulate the production of antibodies and provide immunity against one or several diseases, prepared from the causative agent of a disease, its products, or a synthetic substitute, treated to act as an antigen without inducing the disease.

For our conversation we are going to use two terms that are often interchangeable but have some functional and important differences:

- Inoculation is the act of introducing a virus or pathogen into a person’s body. It can be used in other contexts, such as when a culture is inoculated with body fluids (such as from a nasal swab) to test for the presence of a bacterium or virus.

- Vaccination is the process of introducing a vaccine into the body to produce immunity to a specific disease. Vaccines are usually administered through needle injections but can also be administered by mouth or sprayed into a nostril.

It’s Ancient History

The first recorded vaccine and vaccination program was in 1500 (some sources claim even earlier, 200 BCE) when the Chinese Empire inoculated the infected smallpox population. There are well-documented accounts of Emperor K’ang Hsi having his children inoculated because he was a smallpox survivor due to the practice.  I will admit that the philosophy was sound, but the way they went about it was, well, let’s say it was appropriate for the time. Inoculation would happen when they would take smallpox scabs and grind them into a powder and then blow said powder up the person’s nose to be inoculated. Affective, yes, but far from the sound scientific rigor that our current day vaccines must go through. What may be more impressive is that this inoculation practice continued until the late 1700s, when Edward Jenner, an English physician, scientifically tested his hypothesis that introducing cowpox into the human system would protect them from smallpox. Jenner is credited with coining the term vaccination, derived from the Latin word for cow (Vacca). Jenner’s theories and new terminology were introduced in the Americas in 1800, and shortly after that, mortality rates in both England and America.

I will admit that the philosophy was sound, but the way they went about it was, well, let’s say it was appropriate for the time. Inoculation would happen when they would take smallpox scabs and grind them into a powder and then blow said powder up the person’s nose to be inoculated. Affective, yes, but far from the sound scientific rigor that our current day vaccines must go through. What may be more impressive is that this inoculation practice continued until the late 1700s, when Edward Jenner, an English physician, scientifically tested his hypothesis that introducing cowpox into the human system would protect them from smallpox. Jenner is credited with coining the term vaccination, derived from the Latin word for cow (Vacca). Jenner’s theories and new terminology were introduced in the Americas in 1800, and shortly after that, mortality rates in both England and America.

A Quantum Leap

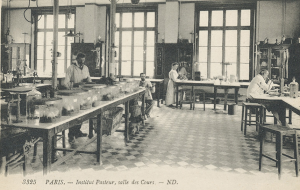

Now we will jump into the mid to late 1800s when scientific methods and understanding of disease process explode, and we see a sharp increase in named diseases plaguing society. The image to the left is of the a view of a laboratory at the Institut Pasteur in Paris (photo from The History of Vaccines website). None of these newly identified ailments were new; we just now had names to put with their devastating effects. The world was now set to deal with Diphtheria (1826), Rubella (1841), Rabies (1831), Cholera (1849), and Pneumococcal (1881), just to name a few. This was a time in history where we see the early pioneers of scientific discovery, like Louis Pasteur, digging deep and expanding our knowledge of the microscopic world. Throughout the rest of the 1800s, our understanding of how we contract and transmit disease was documented, and behavior modification measures were introduced to quell the spread. During this time, many rudimentary vaccines, like the ones listed on the National Institutes of Health website were developed, but few were willing to utilize them due to fear and lack of adequate public explanation.

Now we will jump into the mid to late 1800s when scientific methods and understanding of disease process explode, and we see a sharp increase in named diseases plaguing society. The image to the left is of the a view of a laboratory at the Institut Pasteur in Paris (photo from The History of Vaccines website). None of these newly identified ailments were new; we just now had names to put with their devastating effects. The world was now set to deal with Diphtheria (1826), Rubella (1841), Rabies (1831), Cholera (1849), and Pneumococcal (1881), just to name a few. This was a time in history where we see the early pioneers of scientific discovery, like Louis Pasteur, digging deep and expanding our knowledge of the microscopic world. Throughout the rest of the 1800s, our understanding of how we contract and transmit disease was documented, and behavior modification measures were introduced to quell the spread. During this time, many rudimentary vaccines, like the ones listed on the National Institutes of Health website were developed, but few were willing to utilize them due to fear and lack of adequate public explanation.

Stuck in a Rut, But Not for Long

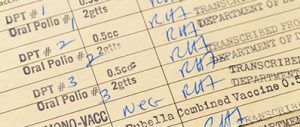

Our vaccine advancements really languish on the vine until the significant push for polio vaccination in the 1950s. Image to the right, from CDC.gov, childhood immunization form. During the 1960s and 70s, we see the newest vaccines come into use as we begin to understand how to culture bacterium and segment viral strains. We see our first standardized childhood vaccine programs rolled out in public health, and we start to see the signs of early efforts to discredit the science. Admittingly this is a vast oversimplification of the science and impact it has had on the world. I would encourage you to visit The History of Vaccines website to do more of a deep dive into the history.

Our vaccine advancements really languish on the vine until the significant push for polio vaccination in the 1950s. Image to the right, from CDC.gov, childhood immunization form. During the 1960s and 70s, we see the newest vaccines come into use as we begin to understand how to culture bacterium and segment viral strains. We see our first standardized childhood vaccine programs rolled out in public health, and we start to see the signs of early efforts to discredit the science. Admittingly this is a vast oversimplification of the science and impact it has had on the world. I would encourage you to visit The History of Vaccines website to do more of a deep dive into the history.

In today’s world, we routinely vaccinate for:

Cholera (1880)

Rabies (1885)

Tetanus (1890)

Bubonic Plague (1897)

Tuberculosis (1921)

Diphtheria (1923)

Pertussis (1926)

Yellow Fever (1932)

Seasonal Influenza (1937)

Polio (1952)

Anthrax (1954)

Japanese Encephalitis (1954)

Adenovirus (1957)

Measles (1963)

Mumps (1967)

Rubella (1970)

Pneumococcal (1977)

Meningococcal (1978)

Hepatitis B (1981)

Varicella (Chicken Pox) (1984)

Haemophilus Influenzae Type B (1985)

Hepatitis A (1991)

Rotavirus (1998)

Human Papillomavirus (2006)

Shingles (2006)

Typhoid Fever (2013)

Malaria (2015)

Ebola (2019)

COVID-19 (2020)

Not everyone ends up getting all of these, but we do (as recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)) get most. To see the full list of recommended vaccine arranged by age and including information about the method and number of times it will need to be administered please visit the CDC site’s vaccine information page. Specific vaccines are determined by geography and the risk associated with travel or residency in a county or region. Polio is one example of regional vaccination. We no longer vaccinate for Polio in the US, but there are parts of the world like Afghanistan which are still dealing with the disease and have active Polio vaccination programs. Nevertheless, it’s quite an impressive list. It only has taken us some 600 years (more or less) to get here. Our development and understanding of infection processes have grown exponentially as to has our ability to mitigate the devastation of the infections.

Stay Tuned

As we move our conversation along, I would like to direct your attention to the top of the blog; as you can see, it is indicated that this is part one (one of three blogs, to be exact). In the next blog, we are going to address the manufacturing and pharmacology of the modern vaccine. This will provide you with context when looking at the efficacy and safety of the process. We will also take some time to look at concerns, dispel rumored side effects, and the longitudinal data on effectiveness.

As we move our conversation along, I would like to direct your attention to the top of the blog; as you can see, it is indicated that this is part one (one of three blogs, to be exact). In the next blog, we are going to address the manufacturing and pharmacology of the modern vaccine. This will provide you with context when looking at the efficacy and safety of the process. We will also take some time to look at concerns, dispel rumored side effects, and the longitudinal data on effectiveness.

To be continued…

Part Two – The Modern Vaccine, Facts Not Fiction

Part Three – Musing of COVID Vaccine Recipients

WOW! Lots of info there. Can’t wait for the next installments! Patiently waiting for my turn to get the shots! 😉